What is iq

High Range IQ Testing

IQ is an acronym which stands for ‘intelligence quotient’. Your intelligence quotient is a number-based score which attempts to estimate your overall intelligence. Intelligence is, however, a very abstract concept to define making your IQ score a broad measure of your intellectual capabilities. IQ scoring represents an individual’s reasoning capabilities across various faculties of cognition and mental processing, as compared to a statistical average.

IQ Score Results

$27

- Your Score

- Your Professional Assessment

- Digital IQ Certificate

Approximately 95% of the populace has an IQ falling between 70 and 130, leaving 2.5% below 70 and 2.5% scoring 130 and above. There are very few people who score in the upper regions of the scale. For example, Mensa is a society which only accepts people in the top 2% of all test takers. This means that only 1 in 400 people stand to potentially make the cut with the minimum IQ falling between 140 and 145.

The IQ Test Origins, Meaning, and Significance

Introduction

-

A Brief History of Intelligence Testing

- Early Developments

- Alfred Binet and the invention of the modern IQ test

-

IQ Testing Today

- The spread of intelligence: IQ scores and the bell curve

- Standard deviation: How common — or uncommon — is your score?

- IQ scores and labels: How many points equals a genius?

- IQ testing and reliability: Can we trust IQ tests to give consistent results?

- IQ testing and validity: Do IQ tests actually measure intelligence?

-

IQ and You

- IQ scores and job status

- IQ scores and job performance

Concluding Thoughts

Sources

So you took an IQ test — now what?

You might be wondering who came up with the test you just took, what your score means, how much weight to give it — there’s certainly no shortage of questions surrounding the famous intelligence test.

Nor is there a shortage of opinions. Indeed, it seems almost everyone has one. It could be based on something they read in a magazine, or heard a friend say. These opinions tend to flock toward one of two extremes: There are those who dismiss IQ tests as worthless, or even worse, positively harmful. And then there are those who view IQ scores with an almost religious reverence, taking them to be the be-all-end-all when it comes to questions of intelligence. (Of course the people who place high importance on IQ tests are often those who’ve scored well themselves.)

With all of these opinions buzzing around, it can be difficult to see IQ tests for what they actually are: useful tools.

Like any tool, an IQ test must be used correctly in order to be of value. But how does one ‘use’ an IQ test? The answer to this question rests on a single word: interpretation. Taking an IQ test can be fun and exciting, but a score is just a number if you don’t know how to interpret it.

One thing this article will teach you is how to interpret a score you received on an IQ test. When you know how to interpret your score, you can ‘use’ IQ tests responsibly, and in turn, get a lot out of them. An IQ score might not be the magical number its most ardent proponents want it to be, but it’s not an arbitrary value either. And when you understand what IQ tests are and what they can and can’t do for us, your score can be more than ‘just a number.’

Before we dive into the fascinating topic of intelligence testing, it’s important to recognize that it’s only natural to have strong feelings after taking an IQ test. These feelings can range from despair to elation, from total credence to scathing skepticism. There’s no shame in feeling any of these things, but it’s important not to let your initial emotional reaction have the final say.

So, take a breath, and let’s take a closer look at IQ tests. As one psychologist and expert on intelligence tests aptly put it, intelligence testing must be intelligent testing, for when it is, we can “understand what IQ tests are and how they can be used as instruments of help.”

Where do IQ tests come from?

1.1 Early developments

Intelligence tests have been around for quite some time. Indeed, we know that Ancient Chinese emperors used them to evaluate candidates for office more than four millennia ago! The impulse to measure groups’ and individuals’ intelligence runs deep in our nature.

However, the history of the modern IQ test really begins in the 1800s, when two Frenchmen — Jean-Etienne Esquirol, a psychiatrist, and Edouard Seguin, a physician — developed mental tests to help identify children with learning disabilities and mental illness. Their work helped legitimize the idea that cognitive impairments are a medical issue, and as such, deserve to be studied in a scientific fashion.

And their contributions were not merely academic. Seguin in particular leveraged his ideas to bring about real social change: after touring France’s ‘lunatic asylums’ on his own dime, he reported back to the French government with shocking accounts of neglect and abuse. His efforts helped bring about sweeping reforms in France’s treatment of the mentally disabled and mentally unwell.

Though significant, Esquirol and Seguin’s work did not bring intelligence testing into the mainstream.

That would happen in the late 1800s, when Francis Galton, half-cousin to Charles Darwin, set up what he called an “Anthropometric Laboratory” at the International Health Exhibition in London. Anyone with a few pence in their pocket could be measured. Galton’s promise: to give paying customers their full biological profile, which included simple physical measurements (height, weight, arm span, etc.), but also, evaluations of things like depth perception, sense of touch, hearing acuity, and reaction time.

This might not sound like an intelligence test, and it wasn’t — not according to modern standards at least. But in Galton’s time, the following line of reasoning held sway: intelligence is the ability to deal with one’s environment, and since we take in our environment through our senses, we can obtain an objective measurement of intelligence by evaluating the strength or keenness of an individual’s senses.

Galton was, for several decades, considered the authority on psychometrics. But his reign would not extend into the 20th century, which saw a revolution in the way intelligence was both conceived and measured.

1.2 Alfred Binet and the invention of the modern IQ test

The reason Galton’s method of measuring intelligence fell out of favor was simple: it was no good. More specifically, it didn’t measure what it claimed to: intelligence. This became painfully clear when, in 1901, a graduate student named Clark Wissler ran a statistical analysis on data collected using Galton’s methods. The result: high scores on the Galton-style intelligence tests did not, in any kind of statistically significant way, correlate with academic achievement.

This was a big problem. If a test is supposed to measure intelligence, we would expect it to produce scores that match real-world markers of intelligence, like GPA.

After Galton’s discrediting, the very idea of intelligence testing was cast into doubt. The intelligence test needed a serious makeover, and a French psychologist named Alfred Binet knew it.

In fact, he knew it years before Galton’s downfall. Throughout the 1890s, Binet worked tirelessly on an alternative method of measuring an individual’s intelligence. Binet believed strongly that we cannot hope to measure something as complex and nuanced as intelligence using the crude tests devised by Galton and his disciples. If we want to know how smart people are, we’ll get nowhere testing their eyesight and hearing. A genuine intelligence test must involve tasks that actually require intelligence — that is to say, ‘higher-order’ cognitive capacities like memory, reasoning, and judgment.

The test that Binet devised, named the Binet-Simon scale (after Binet and his colleague Theodore Simon), took the world by storm and restored the reputation of intelligence testing as a viable tool for psychologists, psychiatrists, educators, and anyone else with an interest in objectively measuring people’s cognitive abilities.

Unlike Galton, who was happy treating intelligence like height or eye color — i.e., as just another biological trait — Binet recognized that intelligence wasn’t so simple or easy to measure. The Frenchman was clear on this point: “The mark of intelligence is . . . not made nor can it be made as one measures height.”

Moreover, Binet understood that intelligence shows up in different ways in different people, and that its manifestation can be influenced by things like personality and temperament. This was a radical idea and it remains at the heart of contemporary IQ testing.

Binet also argued that when it comes to measuring something as elusive and complex as intelligence, some error is inevitable. The idea of pinning down intelligence with the same finality we pin down a person’s height belonged in the 19th-century. We can’t measure intelligence as precisely or reliably as we measure simple physical traits, but that doesn’t mean we should give up on measuring it altogether.

Binet organized the questions on his test into age-based groupings. Questions that most four-year-olds could answer were grouped together, as were questions that most five-year-olds could answer, and so on. Here is a sampling of questions in different age groupings.

- Four years: “Compare the length of two lines”

- Eight years: “Repeat five digits”

- Twelve years: “Give more than sixty words in three minutes”

The Binet-Simon scale exploded in popularity, as evidenced by the proliferation of translations and adaptations that started popping up all across the globe. IQ testing flourished on American soil in particular. During both world wars, the armed forces used an adaptation of the Binet-Simon scale to evaluate millions of draftees. This helped cement IQ testing’s place in American society, as well as demonstrated its usefulness as a tool for measuring the intelligence of the general population in addition to children with mental disabilities.

Translations and adaptations of Binet’s test — most notably, the Stanford-Binet, developed in 1916 by Lewis Terman — dominated the intelligence testing scene until the 1960s, when a test developed by the psychologist David Weschler (the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale: WAIS) skyrocketed in popularity.

Wechsler thought Binet IQ tests emphasized verbal intelligence too much, and thus, included a nonverbal “performance” section in the WAIS, along with numerous subtests designed to test different parts or dimensions of a person’s intellect. The goal was simple, which is ironic — Wechsler’s simple goal was to construct an IQ test that was more sensitive to the complexity of human intelligence than the single-score Binet tests.

There is perhaps more overlap between Wechsler and Binet than there is disagreement. Both men saw intelligence as something complex and difficult to measure, but not so difficult that we can’t develop reliable and relatively accurate methods for doing so.

Their legacy is their tests, which remain in use to this day, along with various other intelligence tests that purport to measure IQ. The fact that IQ tests have survived into the 21st-century suggests that they have distinct value for us, even if they’re not perfect measures of intelligence. But what is this value, and just how imperfect are IQ tests? More to the point: what does your score say about you, and how much weight should you really give it?

Let’s take a closer look at IQ tests themselves . . .

What do IQ scores really tell us?

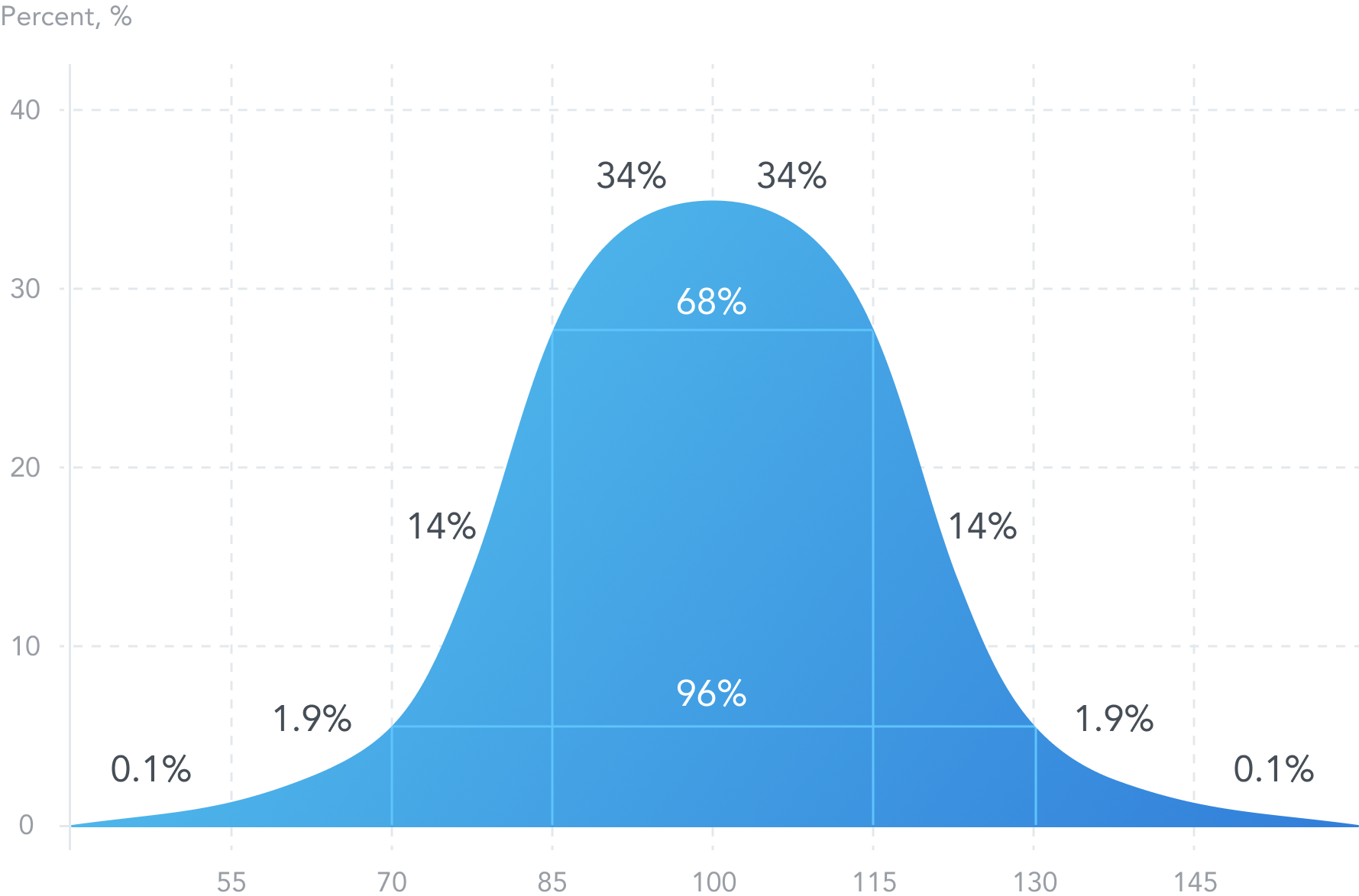

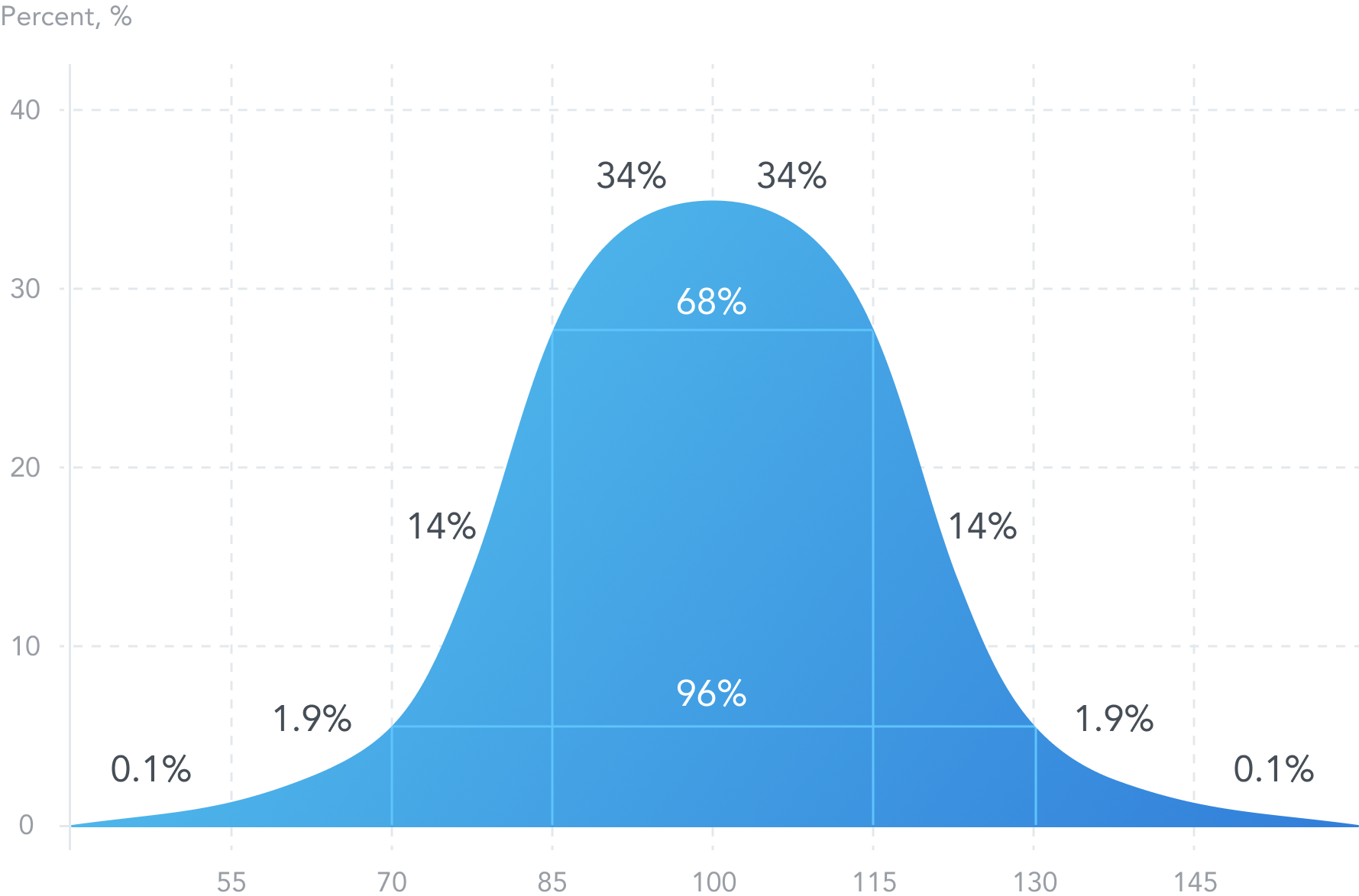

2.1. The spread of intelligence: IQ scores and the bell curve

When you look at a graph of IQ scores, this is what you see: A symmetrical bell-shaped curve that peaks in the middle and gently slopes downward on both sides. Along the horizontal x-axis are the possible scores a person can achieve on an IQ test, arranged from low to high, while the y-axis displays the probability of achieving a given score (the frequency of the score in the population). So, as you trace your finger along the bell curve, from left to right, the height of your finger represents the frequency in the population of whatever score is underneath your finger, on the x-axis.

As you move from very low scores (on the left) to the average score of 100 (in the middle), the frequency of the scores increase — i.e., they become more common. Then, as you pass the top of the bell, the curve slopes down again as the scores get higher and higher.

Many traits display this basic pattern, or ‘normal distribution.’ Take height, for instance. People of average height are abundantly common. People close to average are common, but less so. Then you have people at the extreme ends of the spectrum — the extremely tall and extremely short — who are rare. That’s why there are only a handful of people taller than eight feet, but millions taller than six feet. Height might be easier to measure than IQ, but both traits form the same smooth bell curve when graphed.

But just how common is your score? To answer that question, we need to talk about standard deviation, a pivotal concept for interpreting IQ scores.

2.2. Standard deviation: How common — or uncommon — is your score?

The majority of IQ tests are set up so that the average score people achieve is 100, with a standard deviation of 15. But what’s a ‘standard deviation,’ and what does it tell you about your score?

A standard deviation is a measure of how ‘spread out’ a data set is. To say that IQ test scores have a standard deviation of 15 is to say the following:

- 68% of scores fall within one standard deviation of the average score (100). So, roughly 70% of people score somewhere between 85 (100 - 15) and 115 (100 + 15).

- 96% of scores fall within two standard deviations of the average score. So, 965% of people achieve scores within 30 points of the average score of 100 (i.e., scores between 70 and 130).

- 4% of the population score below 70 or above 130.

Imagine a room filled with 100 people sitting at desks. If all of these people are given a standard IQ test, we can expect about 70 of them to score somewhere between 85 and 115. The word “about” is important here; a normal distribution is a statistical model that tends to map onto IQ scores quite well. It doesn’t mean that for any given sample of people who take an IQ test, exactly 68% of them will score between 85 and 115, exactly 96% will score between 70 and 130, and so on.

Let’s get back to room filled with 100 people. Shouldn’t it matter how old the people in the room are when it comes to their IQ scores? Actually, not really. Your IQ score is based on how your score compares to those achieved by people the same age as you. So, an eighteen-year-old isn’t necessarily going to achieve a higher score than a ten-year-old. This is because both the ten- and eighteen-year-old’s scores are determined by comparing their performances to individuals in their respective peer groups. So, a ten-year-old achieves an exceptionally high IQ score by outperforming almost all other ten-year-olds, not eighteen-year-olds, and vice versa.

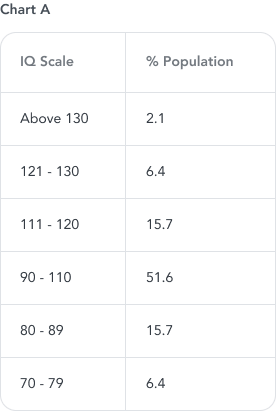

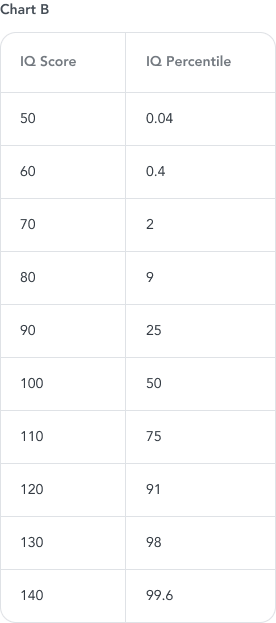

The following charts display typical distributions of IQ scores for a standard IQ test. Chart A shows the percentage of the population whose scores fall within a particular range of scores; chart B shows percentiles, which express the percentage of people who score equal to or below a particular score. In simpler terms, the first chart tells you how many people score similarly to you, while the second tells you how many people score lower (or the same) as you.

Chart B should give you a fairly good idea of your particular score’s percentile. If your exact score isn’t in chart B, and you want more than an estimate of your IQ’s percentile, there are an abundance of IQ percentile calculators available online.

You might not be satisfied knowing things like percentiles. If you’re like a lot of people, you want to know what your score says. As in: what words can be used to describe someone with your IQ. “Am I stupid?” “Am I smart?” “Am I a genius?” It is only natural to wonder such things, and in the following section, we’ll talk about IQ scores and how they can be matched up with common descriptions of intelligence.

2.3. IQ scores and labels: How many points equals a genius?

At the beginning of any discussion concerning the meaning of IQ scores, it’s important to remind ourselves of a simple truth: meaning is a matter of interpretation. In other words, we give IQ scores their meaning, not the other way around. So, what we choose to treat as the cut-off point between ‘genius’ and ‘not genius’ or between ‘normal’ and ‘subnormal’ intelligence is just that: a choice.

There is no objective fact — nothing we could discovery in a laboratory — that could tell us where genius begins, and in fact, thinking about genius (or intelligence as a whole) as something with strict ‘boundaries’ that we can define with total precision might not be a very fruitful — or accurate — way of thinking about thinking.

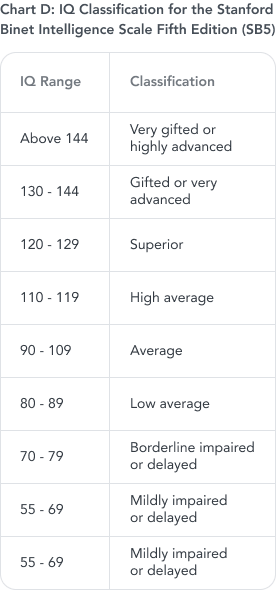

That said, contemporary IQ tests generally do provide classifications of score ranges (see charts C and D).

There seems to be something wrong with Juanita’s approach to interpreting IQ scores. For one, her interaction with Rufus suggests that she takes the classification system too seriously — as eternal truth rather than a set of loose suggestions. But also, and perhaps more importantly, she is overlooking something crucial about IQ tests: If she and Rufus took the same test again tomorrow, Rufus could very well score higher than her.

There seems to be something wrong with Juanita’s approach to interpreting IQ scores. For one, her interaction with Rufus suggests that she takes the classification system too seriously — as eternal truth rather than a set of loose suggestions. But also, and perhaps more importantly, she is overlooking something crucial about IQ tests: If she and Rufus took the same test again tomorrow, Rufus could very well score higher than her.

But doesn’t this undermine the validity of IQ tests as a measure of intelligence? Even if intelligence is not entirely fixed, it doesn’t fluctuate wildly from one day to the next. Someone who’s smart goes to sleep smart, and wakes up smart. Shouldn’t IQ tests reflect this fact? The short answer is yes; IQ tests need to be reliable if they are to be useful. So, are they? The answer is again yes, but things are complicated . . .

2.4. IQ testing and reliability: Can we trust IQ tests to give consistent results?

A reliable measurement technique is simply one that yields consistent results. Measuring height is highly reliable: if you measure someone’s height three times in a row, chances are, the three measurements will be very close to one another, if not identical (unless you wait a long time in between measurements!).

But what about measuring IQ? Is that too a reliable measurement, likely to produce consistent results over time?

Generally speaking, yes, IQ tests are reliable. However, that statement comes with some important caveats.

First, it’s important to note that no IQ test is perfectly reliable. In other words, if you take ten IQ tests, the chances of scoring the exact same on all ten tests is essentially zero. This is because intelligence, unlike height, is a complex phenomenon, and how it manifests in a test-taking situation is affected by a host of factors, including the environment in which the test is given, the way the test is administered, how the test-taker is feeling on that particular day, and so forth.

This brings us to a second important point about reliability: the reliability of IQ testing is compromised when the environment in which tests are given is not controlled. What does this mean? Well, simply this: if you take multiple IQ tests in significantly different situations and circumstances, your score is likely to vary more widely than if you were to take the test under carefully controlled conditions. For instance, if you take an IQ test when there is a crying baby in the room distracting you, and then you take it again a week later in a quiet room where it’s easier to concentrate, chances are your score will be a lot higher the second time around.

This all might sound like common sense, but it’s important to keep in mind, especially if you’ve taken — or plan on taking — an online IQ test. Online IQ tests are not administered by a trained professional. So, when you take an online IQ test, you must, in an important sense, play the roles of both test-taker and test-administrator. This means it falls on you to control the testing conditions. If you live in a noisy apartment for instance, you might decide to take your online IQ test at a library where it’s easier to focus.

The bottom line is this: if you take online IQ tests in conditions that are not controlled, your scores are more likely to be all over the place. So, if you took an IQ test and are now feeling disappointed by your score, ask yourself:

- Did I take the test when I was feeling good (e.g., not tired, motivated, calm, etc.)?

- Did I take the test in a physical environment conducive to concentration (e.g., quiet, free from distractions, physically comfortable, etc.)?

- Are there things going on in my life right now that might interfere with my ability to perform on an IQ test (e.g., health problems, personal issues, etc.)?

If the answer to either of the first two questions is “no” or if the answer the the third question is “yes,” it’s definitely possible that your score was impacted by more than your intelligence. For instance, if you were really tired when you took your IQ test, your fatigue likely influenced your performance and thus your score. If you take the test again when you’re not tired, you could very well score a lot higher.

So, IQ tests are reliable, but not perfectly so, and if you’re taking online IQ tests, it’s especially important to monitor the testing conditions so that you achieve consistent results. Finally, taking multiple IQ tests, as opposed to just one, will give you a clearer idea of what your IQ is. That said, many experts on intelligence testing agree that the idea that each person has a single IQ — one score that perfectly represents their intelligence — is a myth.

Here’s a useful analogy: If you take your blood pressure once in a single year, the result could be highly misleading. For instance, if you happened to take it right after receiving stressful news, it could be much higher than it normally is. Taking your blood pressure every day, on the other hand, or even multiple times a day, will give you a much clearer picture of what your blood pressure actually is. And, like IQ, an individual’s blood pressure constitutes a range, not a single value.

So, if you took an IQ test and aren’t happy with the result, feel free to take more tests — you might find that your performance on the first test wasn’t representative of your true abilities. Taking multiple tests can help you establish what your true IQ range is.

2.5. IQ testing and validity: Do IQ tests actually measure intelligence?

IQ testing might be reliable, but is it valid? The distinction between reliability and validity is important, and can be illustrated with a simple metaphor.

Taking an IQ test is like shooting an arrow at a target. A reliable IQ test yields consistent results — the arrows all hit the same area of the target and are thus clustered together.

But it’s possible for a test to be reliable but not valid. Reliability is about the consistency of results, while validity is about their accuracy. A reliable archer can hit the same part of a target over and over again, but if that part of the target isn’t near the bull’s-eye, the archer can’t be said to be accurate.

Applying all of this to IQ tests, we want these tests to be reliable and valid. That is to say, we want an intelligent test not only to produce consistent results, but results that actually measure intelligence — results that hit the target, so to speak.

There is strong evidence that IQ tests are not only reliable, but valid (i.e., accurate). Statistical analysis has time and again shown that contemporary IQ tests correlate robustly with other important data that we intuitively see as related to intelligence, such as GPA, job status, and job success. This suggests that IQ is measuring something meaningful, even if it’s not a perfect measure of a person’s overall intelligence *.

It’s important to keep in mind that the relationship between IQ and other measures of intelligence isn’t absolute. So, a student who scores high on an IQ test isn’t necessarily going to do well in school and end up with a skilled, high-paying job, just as a student who scores in the lower range isn’t destined to fail in school and end up doing manual labor for meager pay. We will, in the next section, look more closely at the nuanced relationship between IQ and academic/professional success.

Another reason to think IQ tests really do measure intelligence — or at least significant aspects of intelligence — is the content of the tests themselves. Unlike the early ‘intelligence’ tests of the 19th-century, contemporary IQ tests involve tasks that require cognitive skills such as reasoning, memory, and so forth.

However, there are those who doubt the validity of IQ testing as a method of evaluating intelligence. The main objection coming from this camp of skeptics is that IQ tests don’t measure intelligence per se but a specific type of intelligence (i.e., an ‘academic’ variety, or a particular culture’s idea of intelligence).

This is a reasonable objection, but it does not completely undermine the validity or usefulness of IQ testing to the extent that many believe. The following responses to the above objection should make this clear:

Response 1: Contemporary IQ tests, especially Wechsler scales, are sensitive to nonverbal forms of intelligence, not just ‘academic’ intelligence.

Response 2: Culture does influence our definitions of intelligence, and IQ tests certainly contain some cultural bias, but contemporary intelligent testing is constantly seeking ways of minimizing cultural and other forms of bias. In short, IQ tests aren’t one hundred percent objective, but they are constantly improving along with the field of psychometrics as a whole.

Response 3: It’s true — IQ tests don’t measure intelligence in all of its various manifestations and permutations . . . but that’s OK! In fact, David Wechsler himself embraced this, writing that the abilities needed to perform well on his tests “do not, per se, constitute intelligence or even represent the only ways in which it may express itself.” This isn’t a problem because IQ tests aren’t intended to be used as the sole measure of a person’s intelligence, let alone their ability to flourish in school and the workplace. Again, it’s best to view (and treat) IQ tests as a useful tool — one way to measure intelligence, but not the only way.

* Different IQ tests show different levels of success when it comes to predicting things like school achievement and professional success. For instance, Wechsler scales do a better job at predicting students’ grades than another kind of IQ test, Raven’s Progressive Matrices.

Applying the number to your professional life

3.1. IQ scores and job status

You may have heard that it’s possible to predict how well someone will do in school, as well what kind of job they’ll have and how much money they’ll make, using a single piece of information: the person’s score on an IQ test.

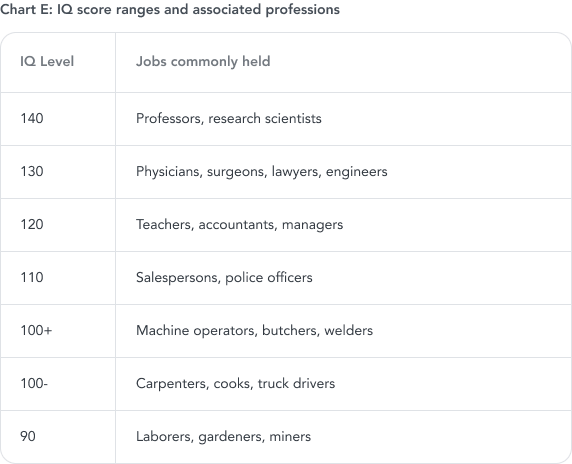

Here is a chart Е displaying jobs that are commonly held by people in different IQ ranges.

This chart should be taken with a grain of salt. If you score 110 on an IQ test, but wish to become a gardener, it’s not as though the above chart says you’re “too smart” for that profession. Similarly, a person who scored 120 on an IQ test who really wants to become a surgeon should do just that — try and become a surgeon! Your own instincts and interests are far more important than a chart based on observed trends.

Also, it’s important to note that the predictive power of IQ scores is highest when those scores are on the extreme ends of the spectrum. What this means is that it’s easier to predict what jobs people with very low or very high IQ scores will go into. For people with IQ scores in the middle range, it is much more difficult to predict job status based on IQ. So, if you take two people with IQs around 100 (the average), it’s not unlikely that they will have very different jobs. One of them might be a doctor, and the other an unskilled laborer.

3.2. IQ scores and job performance

IQ scores are better at predicting job status than they are job performance. In other words, knowing someone’s IQ helps us predict what kind of job they have or will have better than it helps us predict how good the person is at their job, whatever it turns out to be. This is because job performance depends on much more than IQ, and indeed, much more than intelligence. Here are some factors that can influence professional success just as much, if not more, than IQ:

Motivation

A person who lacks motivation, regardless of their IQ, will have trouble performing well at their job. Conversely, a highly motivated individual can outperform colleagues with higher IQs.

Dedication/Perseverance

A person who is truly dedicated to a particular career path can have more success than someone on the same path who has a higher IQ. The reason is simple: effort and persistence go a long way in this life.

Emotional and Practical Intelligence

A common critique of IQ tests is that they don't measure intelligence as a whole, but merely ‘academic’ intelligence. There is something to this critique, and indeed, many proponents of IQ tests — including David Wechsler himself, whose IQ tests changed the landscape of contemporary intelligence testing — accept that IQ tests are a poor measure of certain types of intelligence.

In particular, IQ tests seem to overlook both “practical intelligence” as well as “emotional intelligence” (commonly referred to as EQ). This limits the effectiveness of IQ as a predictor of job success in professions that require high levels of practical and emotional intelligence.

Indeed, it has been shown that IQ scores predict job success much better for academic type jobs (e.g., lawyer, doctor, professor) than for other types of jobs. For instance, studies suggest that emotional intelligence, or EQ, makes a much bigger difference for sales jobs than IQ. This is intuitive, given that being good at sales relies much more on people skills than academic intelligence — or, to put it colloquially, on ‘street smarts’ more than ‘book smarts.’

IQ tests generally involve questions and tasks with clear-cut, single solutions. This doesn’t exactly mirror the ambiguous and messily complex situations that arise on the job in real life. If you work in a kitchen, and something is on fire, abstract reasoning skills will be of little use compared to practical intelligence, which can be thought of as an ability to navigate problems in the real world, using whatever resources are at hand.

So, bottom line — if you’re worried that your IQ score means you’re not going to be professionally successful, just remind yourself: a high IQ is only one of many factors that helps people in the workplace, and its importance varies a lot by job type.

You’re more than a number

You’re more than a number. You’re a complex, unique human being, whose mental abilities form a dazzling array. Your IQ is only one piece of the puzzle that is your mind. Knowing your IQ can help you deepen your self-understanding, but without proper interpretation, it’s just a number. It cannot be understood in isolation from other facts about yourself. In deciding what your IQ says about you, it’s important to embrace your own agency and arrive at your own conclusions. An artist may insist on their genius despite not scoring well on an IQ test, and conversely, someone who scores well on an IQ test may not embrace the term genius.

At the end of the day, you are the one with the final say, not a test. With that said, be open to learning new things about yourself from the IQ test, which continues to undergo refinements and improvements. For if psychology can do anything for us, it's to show us things about ourselves we couldn’t see before.

Binet, A., Simon, T., Kite, E. S. (1916). The Development of Intelligence in Children: (the Binet-Simon Scale). United States: Williams & Wilkins.

Cancro, R (ed.). Intelligence: Genetic and Environmental Influences. (1971). United Kingdom: Grune & Stratton.

Cherry, K. (2020, August 3). Do You Have a Genius IQ Score? Verywell Mind. https://www.verywellmind.com/what-is-a-genius-iq-score-2795585.

Du Plessis, S. (2021, May 16). IQ Tests; IQ Scores Explained; Increasing IQ - Edublox Online Tutor: Development, Reading, Writing, and Math Solutions. Edublox Online Tutor | Development, Reading, Writing, and Math Solutions. https://www.edubloxtutor.com/iq-test-scores/.

Gardner, H., Kornhaber, M. L., & Wake, W. K. (1996). Intelligence: multiple perspectives. Harcourt Brace College Pub.

Hattie, J., Fletcher, R. B. (2011). Intelligence and Intelligence Testing. United Kingdom: Taylor & Francis.

Kaufman, S. B. (2013, July 15). In Defense of Intelligent Testing. Scientific American Blog Network. https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/beautiful-minds/in-defense-of-intelligent-testing/.

Rain, R. (2020, December 4). IQ Percentile Calculator. Omni Calculator. https://www.omnicalculator.com/health/iq-percentile.

Resing, W.C.M., & Blok, J.B. (2002). The classification of intelligence scores. Proposal for an unambiguous system. The psychologist, 37, 244-249.

Van Thiel, E. (2019, May 19). IQ Scale explained, what does an IQ Score really mean? https://www.123test.com/interpretation-of-an-iq-score/.

Wikimedia Foundation. (2021, May 17). IQ classification. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/IQ_classification.